What do We Know About How Processes of Desistance Vary by Ethnicity?

A Review of Current Knowledge

Introduction

Since just before the turn of the century, criminologists have started to explore in depth the processes by which those people who had become enmeshed in the criminal justice system stopped offending. Up until that point, most criminological theories of offending (and when I write ‘most’ I really mean ‘pretty much all’) had focused on why they started to offend (aka ‘onset’). Focusing on why people cease offending (aka ‘desistance’) therefore started to turn thinking and theorising on it’s head. It is also a lot more useful, one could argue, for probation services, prisons and courts in terms of deciding how they might be able to encourage people to stop sooner (and no, just for the record, sending people to prison for longer, does not appear to help people stop in the long term).

Since that time (when people started to ask ‘why do people stop offending?’) we have seen an increase in both studies generally and an increase in the specialisation of such studies. As such, there have been studies of the desistance by burglars, car thieves, sex offenders and so on. There are also studies of female desistance as opposed to male desistance (men commit the vast amount of crime, of course, so the tendency was to focus on men initially, but the inclusion of females is a useful corrective), and more recently, studies of desistance by younger people, sometimes adolescents.

What the literature, oddly, hasn’t devoted anywhere near as much attention to is the study of the ways in which ethnicity might shape or influence processes of desistance. I write “oddly” as it is odd, I think, given how much of the daily traffic of the criminal justice systems in many industrialised and post-industrialised countries is made up of ethnic minority groups in each of these countries that matters relating to ethnicity have not been widely explored. This is not, let me be clear, to suggest that these individuals or the ethnic groups which they are drawn from are any more likely to offend (far from it), but rather to ponder the question as to why sustained and large scale research on desistance and ethnicity hasn’t been undertaken sooner.

Where have we got to?

Along with a small number of colleagues, I have recently embarked upon a study which will explore the processes of desistance for three ethnic groups in Britain. This is funded by the Leverhulme Trust (as grant 2023-241). The groups which we are going to focus on are ‘white’ people, ‘Black’ people and people of Asian descent (that is, in the British context, Bangladeshis, Indians and Pakistanis). Ahead of this, and what the rest of this post is about, we reviewed what is known about processes of desistance and their variations by ethnicity. This will be published in due course by the Howard Journal of Crime & Justice . Below, I summarise our key conclusions here (sorry, you’ll just have to read the original paper to find out how we came to these conclusions or if you agree with the basis on which we reached them! ;-) ).

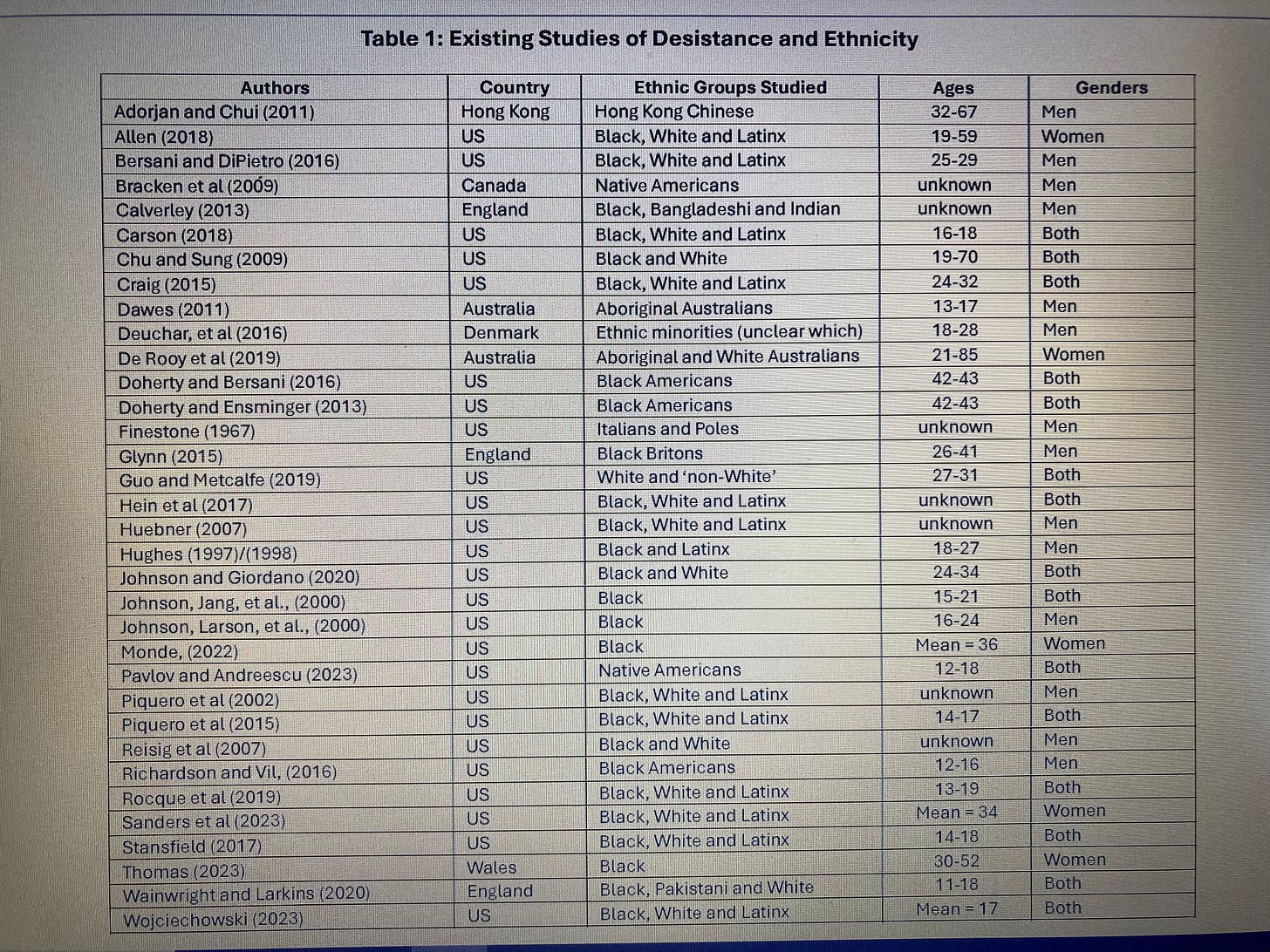

In all, we found just over 30 studies which examined desistance and ethnicity (I’ve rather crudely added a screen shot of the Table from the paper here):

Now, 34, you might think sounds quite a lot. (BTW, if you know of a study which I’ve missed, please do drop me an email with details, and ideally a PDF of the paper - stephen.farrall@nottingham.ac.uk - thank you!).

However, when we exclude US studies (the bulk - at about 25) as the ethnic groups there do not really match those in the UK (we’re, sadly, not blessed with lots of Hispanic people), or those where first nationals are the focus (Australia and Canada - 3 between them) and where processes of colonialization may play a big part in their ensnarement in the criminal justice system, then we’re left with 1 study in Denmark, 1 in Hong Kong, 1 in Wales and 3 in England. If we then look at the ethnicities involved and the ages of the respondents in just the British studies, we see either studies which focus on one ethnic group (like Martin Glynn’s excellent study of Black men), or more recent Thomas’ study of Black women in Wales, or studies which have a range of ethnicities, but which have a rather young sample (like Wainwright and Larkin’s study). Many studies did not have a follow-up either, so change in desires to desist and the impact of structural impediments on these cannot be considered.

All in all then, that initial 35 or so soon melts away. Even in the US, many studies are either quantitative (and often longitudinal, but miss the ‘voice’ of the respondents in the way qualitative research does), or are smaller N qual’ studies which often don’t have a follow-up. Of course, we could have drafted a paper which sounded off on how ‘white’ criminology has again over-looked the experience of ethnic minorities, but we didn’t.

Instead, we wrote an application for research funding.

I’m not going to go into all of the details of what we’ll do, as fieldwork has barely started - and that will need to wait for another post many, many months in the future as we are engaged in a longitudinal study. Instead, I’m going to report some of the findings from the review which the Howard Journal of Crime & Justice have published.

What does our review of the existing literature suggest?

Lets start with some of what we concluded about the methodological basis on which these findings were based (people familiar with my past work, will know that getting the methodology right is crucial):

As mentioned above, most of the studies we have been able to locate are based on North American data (and especially from the USA). This, in and of itself is not a weakness, but rather, highlights a geographical bias which may mean that processes which operate in the US are assumed to operate in other societies. This is especially important given the ways in which US society and the criminal justice system has been shown to exclude many ethnic minority groups and to draw more of them into the justice system.

Many of the studies reviewed rely on samples of people under the age of 25 (check the table above - of those where an age was given, I counted 11 which were reliant on samples exclusively under the age of 25 and only 6 in the sample was exclusively over 25). This mean that the samples in these studies may not yet have reached the end of their offending careers (and, as such, run the risk of inadvertently producing a faulty set of conclusions - after all, we want to know why people have stopped - not simply ‘paused’ their engagement in crime).

In some cases, the operationalisation of desistance was rather weak (such as a month of abstinence from drug use). Of course, there is no one simple operationalisation of desistance - some people use two years crime-free, others want to see a sustained reduction of offending over time and others use other operationalisations.

About half of the studies we located included women in their samples. This is good news, but virtually none of these had been conducted in Europe. The interpretation of gender in this literature was often simplistic, typically framing it in terms of traditional male and female pathways, without fully considering the intersection of both ethnicity and gender with other factors or processes.

There was a focus on ‘street’ offences (as might be expected given both the largely urban location of many ethnic minorities in post-industrialised countries, and the lower than average penetration of some ethnic minority groups into position of power which might enable the commission of ‘white collar’ offences). Most studies of desistance are likewise focused on ‘street offenders’, but there are some studies of ‘white collar’ desistance.

The theories which had been developed since the mid- to late-1990s had not been re-imagined to include the experiences of ethnic minorities, meaning that many were ‘colour-blind’.

The literature neglects how colonial legacies contribute to the structural and systemic biases that impact ethnic minority communities. Colonial practices, such as the historical criminalisation of certain ethnic groups continue to influence policing, judicial treatment, and societal stigma in post-colonial countries and among diasporic communities in the West. Studies risk reinforcing these biases by treating ethnic differences in desistance as isolated or “cultural” rather than understanding them within the context of colonial histories and systemic inequities.

In terms of the substantive findings reported in the above literature, we concluded that:

The main correlates and associates of desistance still hold in many cases, although some (such as the role of religion or the importance of employment) may be nuanced in some cases.

As an example, the role of marriage may vary by ethnicity given that in some communities, men with convictions may be so common (due to their being ‘locked out’ of many employment careers and their levels of ‘over-policing’) that women may find it hard to form relationships with men who do not have convictions. As such, marriage may have a different relationship to engagement in crime.

The levels of capital enjoyed by communities may vary in both form and extent, meaning that processes of desistance may be delayed or altered for some trying to desist in those communities which are economically impoverished.

The role of religion in processes of desistance may vary from community to community due to the nature of the religious belief system (which may or may not tolerate some forms of deviancy) and because some ethnic groups may have a different prevalence of ‘take up’ and differing degrees of belief. In other words, not all religions impact equally upon the lives and life-courses of those who believe in them.

If engagement in crime is widespread in a community (due to structural blockages), then those wishing to desist may need to socially isolate themselves from those routinely engaged in crime.

The criminal justice system, which tends to operate to draw young men from disadvantaged communities and from particular ethnic backgrounds into it’s ambit, may serve only to reinforce negative identities and as such, to make desistance harder for some people.

So, to wrap up, whilst as a community we know ‘a bit’ about how ethnicity might shape desistance from crime, we’re still a long way off being in a position to say with any degree of certainty how one’s ethnicity might shape routes out of trouble. We hope to contribute to that in due course, but for now we’re hoping to immerse ourselves in data collection. Watch this space …