Connecting Crime and Change at the Macro-Level to the Life-Courses of Citizens

Developing a New Approach to Exploring Criminal Careers

Linking Peoples’ Lives with Wider Structures

For decades, criminologists studying what is termed ‘criminal careers’ (that is, the offences which an individual will commit over time) have sought to explain why some people start to offend and others do not. What they found were lots of things which are all now well-known (poverty, lack of opportunity, poor schooling outcomes, their gender and some personality types were all shown to increase the chances of an individual starting to offend). Recently, I and some colleagues started to explore the extent to which the social and economic policies which a national-level government pursued might not also have a role to play in kickstarting individual criminal careers. After all, if people commit crime because of poor opportunities, and if opportunities are a function of governmental policies, then governments might be shaping who and how many people start to offend in unrecognised ways ...

So, our project was essentially one of linking individual factors (the micro-level) with what governments did (or didn’t do) - the macro-level. However, in addition to that, we were looking at changes in peoples’ offending over time since many people will start to offend in their adolescence, reach a ‘peak’ of offending around 20-25 years of age, and then start to decline in terms of the frequency and severity of offending … and so that sent us off towards life course studies. We also wanted to incorporate thinking about how public policies shaped the environments people grew up and lived in.

Of course, the life-course perspective has had a profound impact upon criminological theorising since the early-1990s. In fact, a considerable degree of contemporary criminology’s theoretical tool-box is borrows heavily on the insights of life-course scholars who will be known to many in the social sciences (such as Giele and Elder, 1998, Elder and Pellerin, 1998). This (non-criminological) use of the life-course perspective has traced the links between macro-level social and economic history and social structures, and the lives of both adults and children and the communities they live in. Indeed, life-course studies were borne out of a need to explain how some peoples lives were shaped by the Great Depression in the US. And, as Elder, Modell and Parke note, periods of rapid social change can affect the timing and sequence of events in the transition to adulthood (1993:10). They went on to add that “social-contextual factors have an important impact on the operation of non-social processes” (1993:11). In short, social contexts and changes in these, especially if undertaken rapidly, can affect key events and processes in an individual’s life.

Elder and Giele (2009:8-15) outlined a number of aspects of the life-course perspective, such as the need to locate people (individuals, subgroups or age cohorts) in specific communities at specific historical periods (2009:9). This forces one to recognize that individuals are not isolated and are embedded in wider social contexts and relationships. The focus on wider social and economic structures (Elder 1995) highlights the fact that individuals’ lives are linked to one another. As such, events and long-term trajectories in the lives of parents in a family may alter the life-courses of their offspring.

Yet, as German sociologist Karl Ulrich Mayer noted, the “unravelling of the impacts of institutional contexts and social processes … on life-courses has hardly begun” (2009:426). And when we started down this road (in about 2016 or so) that was still the case. Mayer added that “we know next to nothing about how the internal dynamics of life-courses and the interaction of developmental and social components of the life-course vary and how they are shaped by the macro contexts of institutions and social policies.” (p426, emphasis added). That appears still to be the case, so as well as helping our thinking about criminal careers, our approach may be of use and interest to others.

Life-Course Criminology in Criminology

To recap, whilst life-course criminology had focused on institutions such as families, schools, employers and communities, other institutions and organisations (such as governments, the policies and philosophies which they promote and the policy vehicles for delivering on political aspirations), had not received much attention at all. In other words, the role of welfare regimes, specific social and economic policies, the discourses and policy ‘tones’ adopted by governments and the immediate and longer-term impacts of these, has therefore been missing from our accounts of why some people commit crime. To address the ways in which the same policies may impact upon different people and different cohorts of people, we drew upon Historical and Constructivist Institutionalisms.

Drawing Upon Historical and Constructivist Institutionalisms

Historical Institutionalism is concerned with illuminating how institutions and institutional settings mediate the ways in which processes unfold over time (Thelen and Steinmo, 1992:2). Hall defines an institution as “the formal rules, compliance procedures, and standard operating practices that structure the relationship between individuals in various units of the polity and economy” (1986:19). For others, the focus of historical institutionalism is on the state, government institutions and social norms (Ikenberry, 1988:222-223). Sanders notes that “If [historical institutionalism] teaches us anything, it is that the place to look for answers to big questions … is in institutions, not personalities and over the longer landscapes of history, not the here and now” (2006:53). Historical institutionalism, then, is an attempt to develop understanding of how political and policy processes and relationships play out over time coupled with an appreciation that prior events, procedures and processes will have consequences for subsequent events.

More recently, another body of ‘institutionalist’ thinking has emerged out of a dialogue with historical institutionalism, inspired by Hall’s more ideationally-sensitive approach (Hall, 1992). Going under the name of ‘constructivist’ institutionalism, this argues, that historical institutionalism overlooks the role ideas play in shaping political outcomes (Hay, 2011). This framework focuses on the ways in which ideas, rather than agents, can change or mould institutions and processes. In short, ideas can also influence institutional processes. By bringing a focus on ideas into play, constructivist institutionalism forces us to grapple with the concept of ideational path-dependence (as well as institutional path-dependence, Hay 2011:68-69). Blyth (2002:15) argues that “ideas give substance to interests and determine the form and content of new institutions”. In this way, and akin to theories of the middle range in sociology (i.e. similar to the work of Anthony Giddens, Pierre Bourdieu or Nico Mouzelis), actors are viewed as being active (Hay 2011:71) in that they make decisions, have interests, goals and aims. This begged the following questions:

1: Can (and do?) ideological influences shape countries’ paths through time? Do ideas matter to the policy directions a country adopts?

2: Do national-level paths shape the life-courses of individuals? If so, which intra-cohort groups might be most affected? Do intra-cohort differences have a spatial dimension?

3: Turning to inter-cohort analyses, to what degree have legacy effects (Farrall et al 2020) shaped the life-courses and engagement in crime of successive cohorts of citizens?

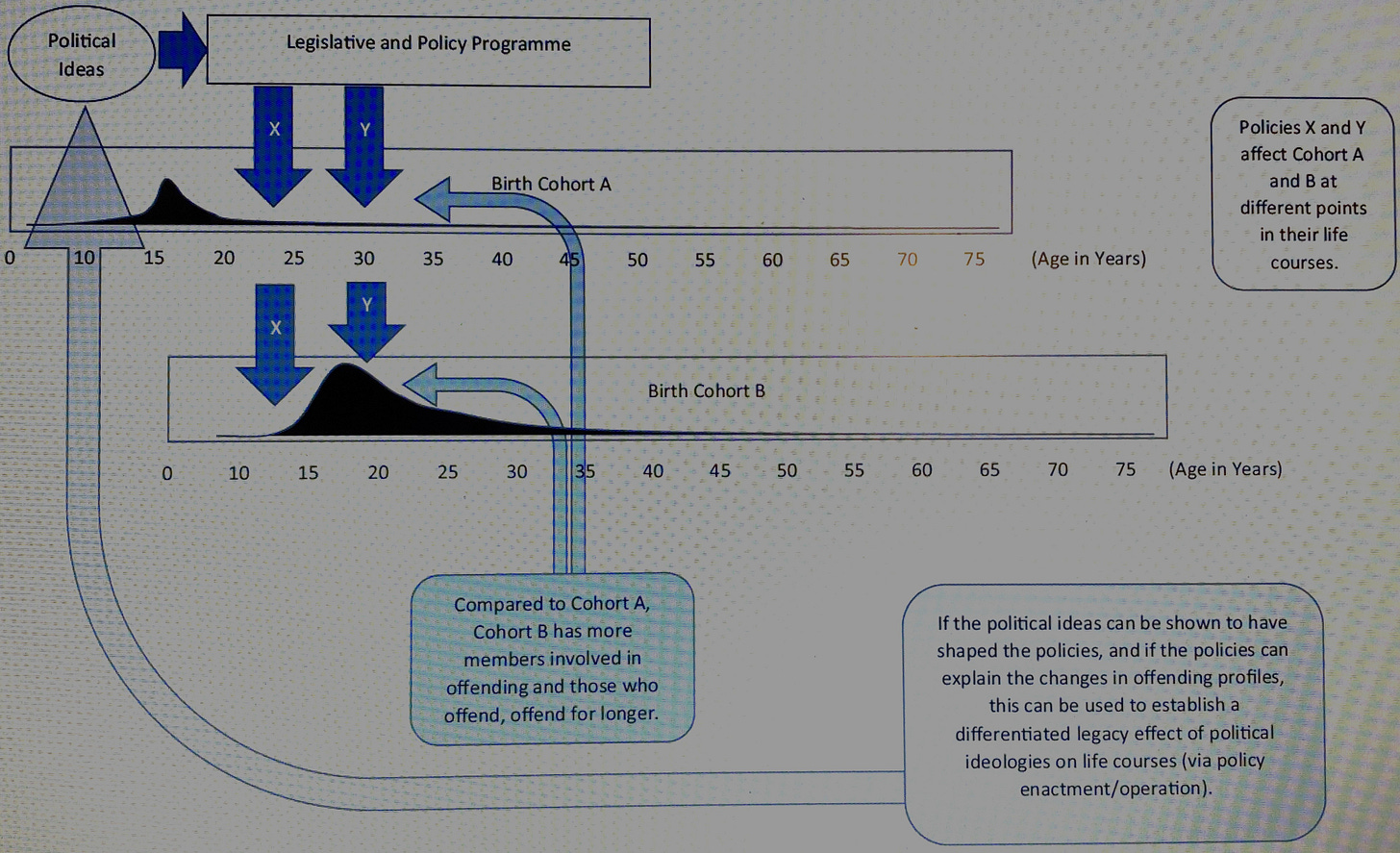

The framework we adopted is shown in Figure One, and specifically relates to our studies of the immediate and long-term impacts of Thatcherism. The figure illustrates how political ideas (developed and expressed when the individuals in Cohort A were very young) may have produced legislation and policies which came into force in their 20s and 30s. As such, these ideas and policies did not affect the numbers of people in that cohort who offended. The same legislation and policies, however, did affect the offending of Cohort B (born 15 years later in our diagram). If, as the box in the rightmost bottom corner states, the ideas can be shown to have shaped the polices, and these can be used to explain the differences in rates and durations of criminal careers between Cohort A and Cohort B, then one might conclude that ideologically-induced policy changes shape different cohorts’ offending trajectories (producing Inter-Cohort Effects). Keeping in mind the fact that in any society there will be variations within any birth cohort due to gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic status, and further that these may also be spatially-clustered, it is easy to imagine how Intra-Cohort Effects may also be present.

Figure One: thinking about how to detect national-level changes impacts on life-courses

So, What Did We Find?

Using two cohorts of people born in Britain, one in 1958 and one in 1970, and who were and still are being followed up, we found evidence that the policies pursued by the Thatcher governments of 1979-1990 and by extension that of the Major governments (1990-1997) did indeed shape individuals’ life-courses and that this a) was due to the social and economic policies which they pursued and b) was associated with an increase in engagement in crime for the later cohort - who were in their formative years during the 1980s (when they were aged 10 to 20). You can read more about the thinking behind the model I sketch above and the other papers we drew upon to support these claims here:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/17488958221126667

In short, the thinking we developed by combining insights from historical and constructivist institutionalisms and the wider work on life-courses (coupled with two excellently collected and curated longitudinal data sets) suggested that our thinking was correct.

Other related publications can be found here:

On Housing:

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv088

On Schools and Truancy:

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz040

On Criminal Careers:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0032329220942395

References

Elder G (1995) The life-course paradigm. In: Moen P, Elder G and Luscher K (eds) Examining Lives in Context. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 101–139.

Elder G and Pellerin L (1998) Linking history to human lives. In: Giele JZ and Elder GH (eds)Methods of Life Course Research. London: SAGE.

Elder G, Modell J and Parkes R (1993) Studying children in a changing world. In: Elder G, Modell J and Parkes R (eds) Children in Time and Place. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 34–308.

Farrall S, Hay C and Gray E (2020) Exploring Political Legacies. London: Palgrave.

Giele Z and Elder G (1998) Life course research. In: Giele Z and Elder G (eds) Methods of LifeCourse Research. London: SAGE.

Hall P (1992) The movement from Keynesianism to monetarism. In: Steinmo S, Thelen K and Longstreth F (eds) Structuring Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 90–113.

Hay C (2011) Ideas and the construction of interests. In: Beland D and Cox RH (eds) Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 65–82.

Ikenberry GJ (1988) Conclusion: An institutional approach to American foreign economic policy. In: Ikenberry GJ, Lake DA and Mastanduno M (eds) The State and American Foreign Policy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 219–243.

Mayer K (2009) New directions in life-course research. Annual Review of Sociology 35: 413–433.

Thelen K and Steinmo S (1992) Historical institutionalism in comparative politics. In: Steinmo S, Thelen K and Longstreth F (eds) Structuring Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–32.